Miriam Schapiro with her contribution to Artists as Collectors at André Emmerich Gallery, 1958. Photo by Lee Boltin.

B. TORONTO, ONTARIO, CANADA,1923

D. HAMPTON BAYS, NEW YORK, 2015

Miriam Schapiro is widely known as a pioneer of the Women’s Art Movement and a leading force in American post-World War II art. Following her formal training at the University of Iowa, she moved to New York with her husband, Paul Brach and integrated into the New York School. Recognized for her colorful and sensuous abstractions of this period, Schapiro showed regularly at André Emmerich Gallery, where in 1958, she was the first woman to have a solo exhibition. Despite considerable success, she felt an outsider to the male-dominated Abstract Expressionism scene and her work of this period explores themes of feminine interiority.

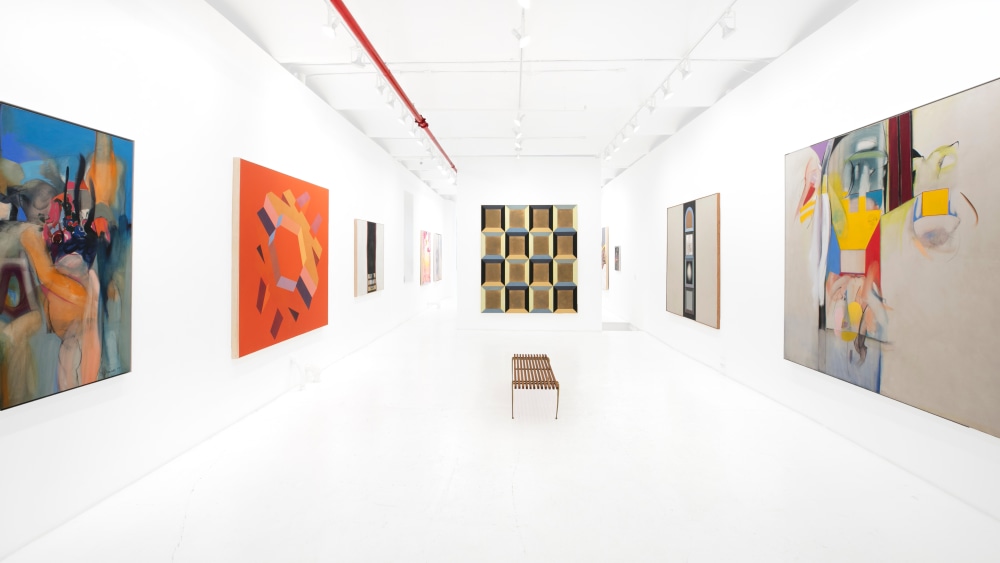

Installation view of Miriam Schapiro, The André Emmerich Years: Paintings from 1957-76, Eric Firestone Gallery, New York, 2023.

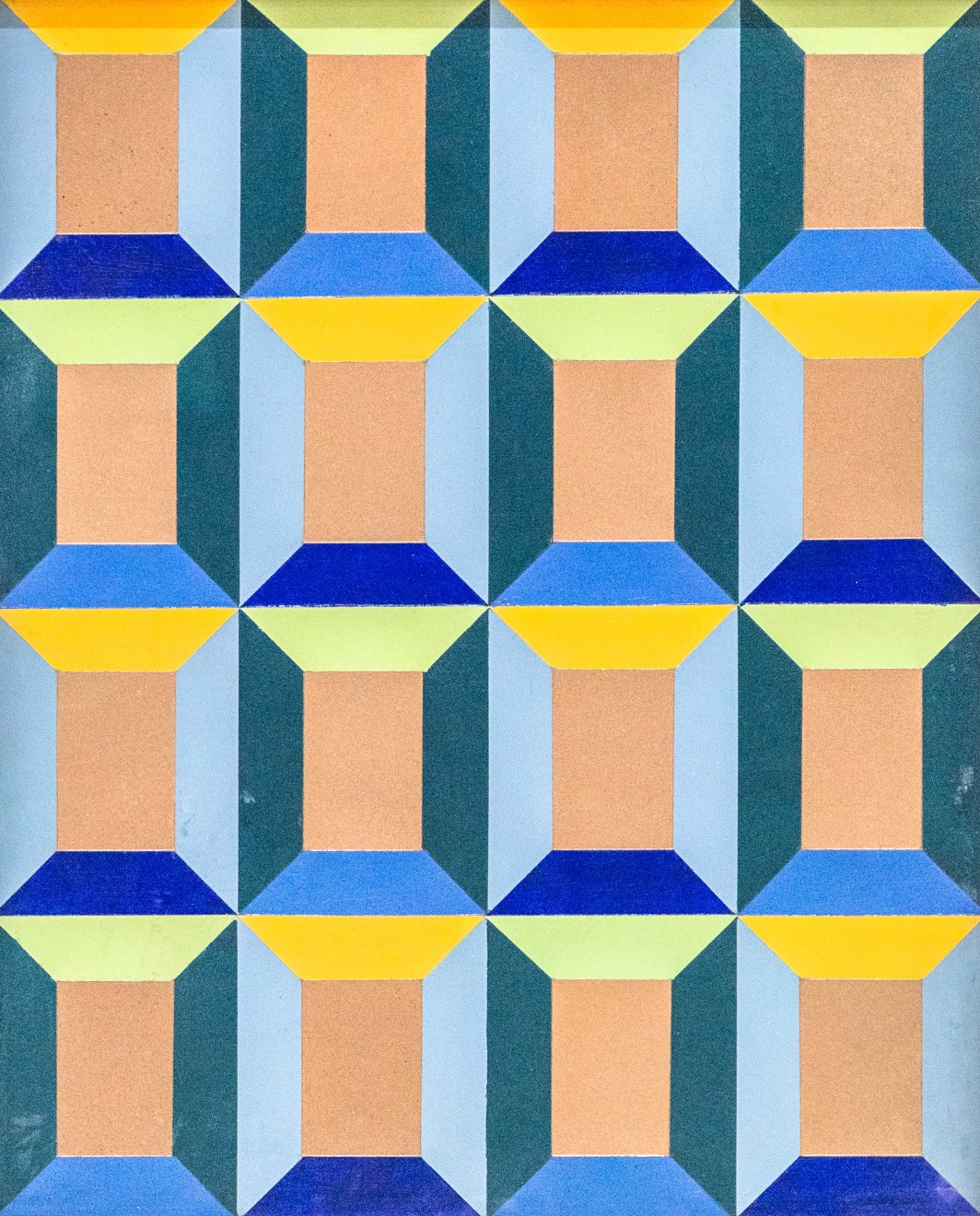

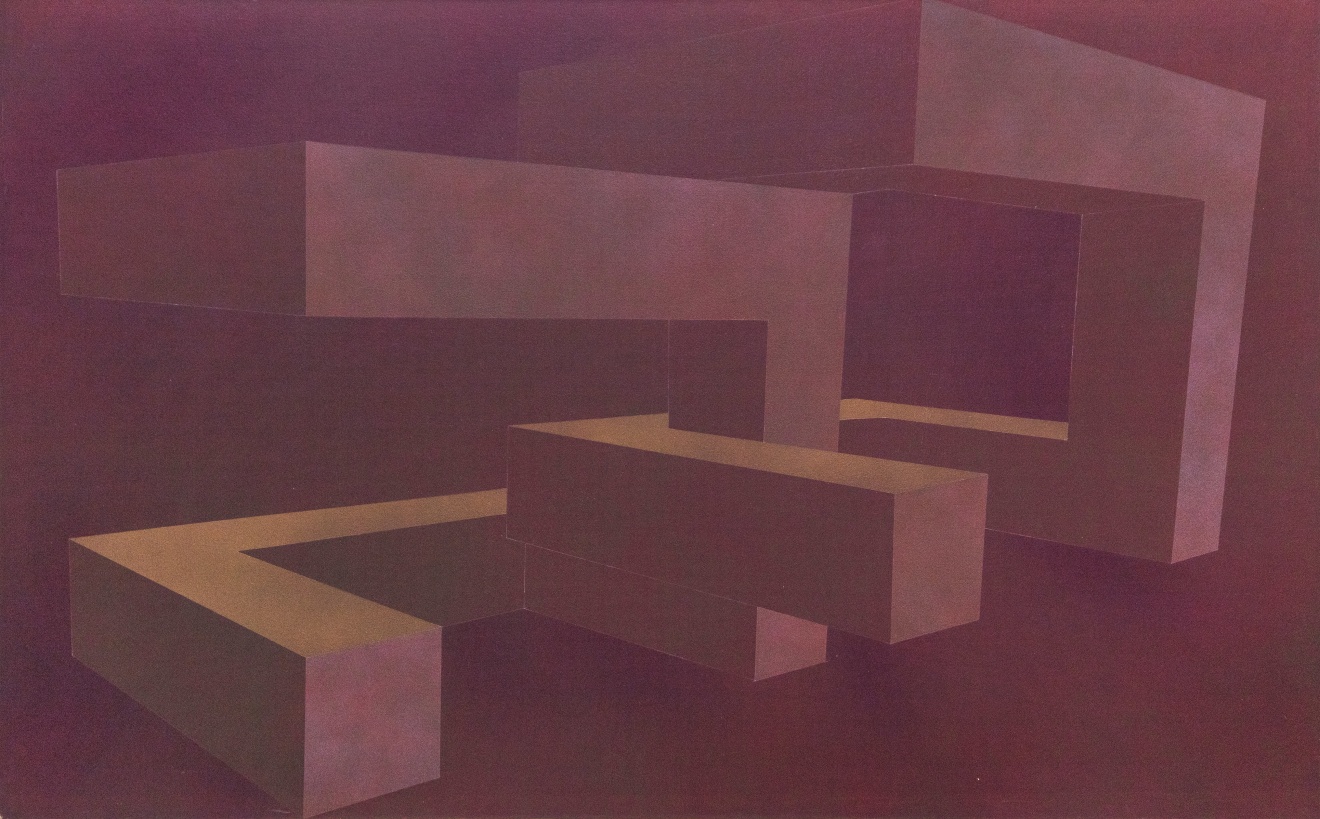

In 1967, Schapiro moved to California where she became a lecturer at University of California San Diego. Here, she was exposed to a scientific community at the university and cool West Coast formalism. Inspired by her coastal, sun-soaked landscape, Schapiro transformed the bright colors, seascapes, and modern architecture of Southern California into monumental hard-edge paintings. Connecting with computer physicists, Schapiro commissioned a custom program that allowed her to transform her hand-drawn shapes through digital manipulation into new distortions, which she then painted.

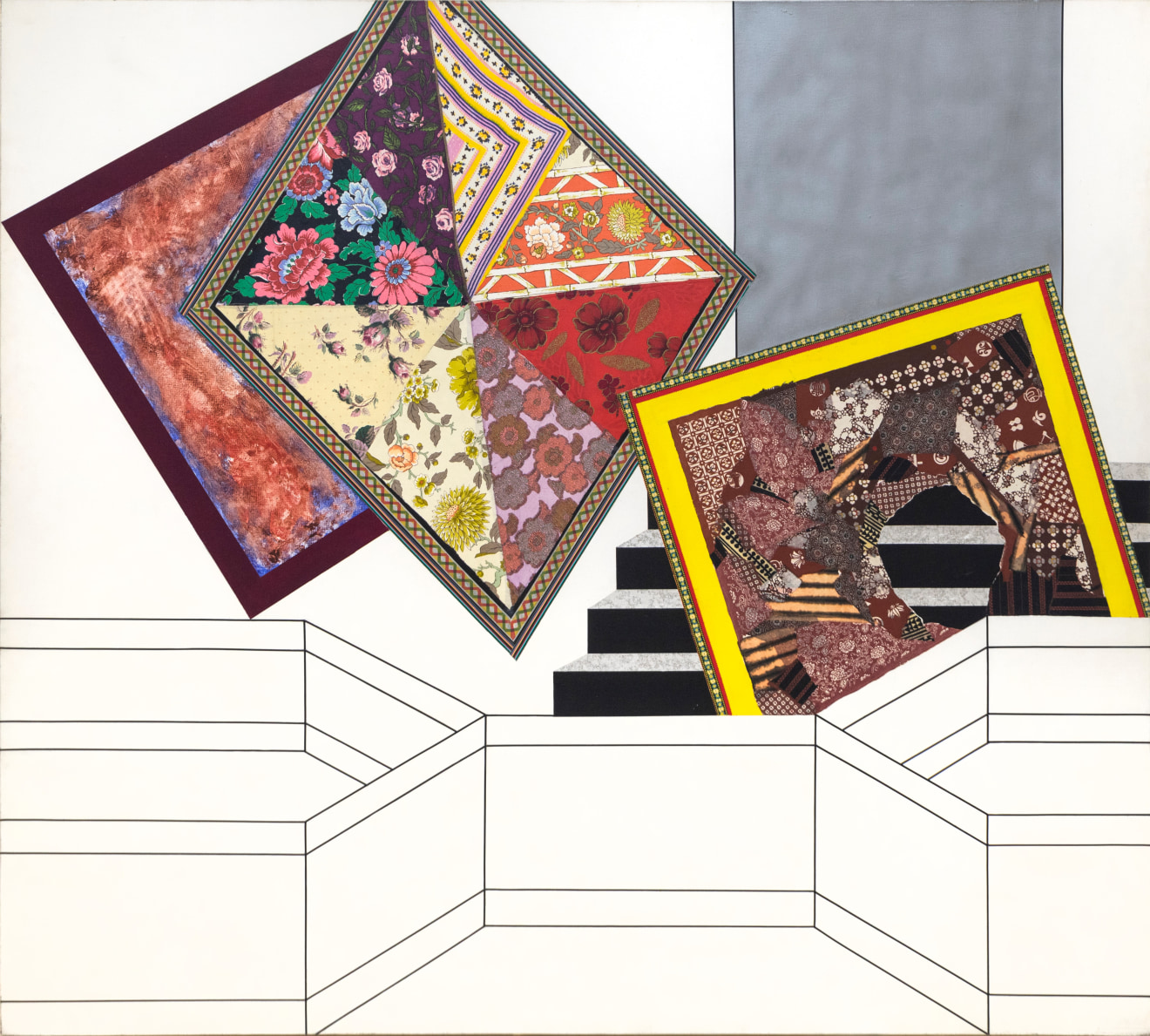

In 1972, Schapiro came to CalArts where, along with Judy Chicago, she formed the Feminist Art Program, a radical curriculum for women art students. The program’s first class produced the landmark exhibition, Womanhouse, an installation and performance space that gained international attention and remains a landmark for the feminist art. Upon returning to her studio practice, Schapiro incorporated collage into her formal compositions using gendered materials to create her signature femmages. Continuing in this vein, Schapiro became a founder of the Pattern and Decoration movement in the mid-1970s.

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Schapiro explored the decorative, often working with collaged materials of lace, sequins, chintz, and other ornamental elements. Getting further away from traditional painting traditions, she created shaped works including her iconic heart, fan, and kimono works. Committed to a feminist imperative, Schapiro travelled around the country lecturing on feminism and art, earning the nickname “Mimi Appleseed.” Schapiro remained active into the early 2000s, integrating themes of art historical ‘collaborations’, theater, and her Jewish heritage into her later work.

Schapiro has been the subject of numerous exhibitions and her work is held in collections worldwide, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Museum of Modern Art (New York), the Museum of Fine Art (Boston), and the Peter and Irene Ludwig Collection, Germany. In 2018, the Museum of Arts and Design in New York presented Surface/Depth: The Decorative after Miriam Schapiro, presenting Schapiro’s femmage work alongside the work of contemporary artists. In 2024 she was included in four separate museum exhibitions focusing on art and technology: Particles and Waves: Southern California Abstraction and Science, 1945–1990 at the Palm Springs Art Museum; Radical Software: Women, Art & Computing 1960–1991 at Mudam Luxembourg (traveling to Kunsthalle Wien); Electric Op at Buffalo AKG Art Museum; and The Living End: Painting and Other Technologies, 1970-Present, at the MCA Chicago. Schapiro is also the subject of a focused survey on view at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami, FL.

Miriam Schapiro: 1967–1972 features a concise selection of Schapiro’s monumental paintings, examining a crucial period of development in the work of the legendary feminist artist. The works on view from this time see Schapiro’s hard-edge geometric abstraction evolve into her gendered, anthropomorphic “central core imagery” and lay the groundwork for her explorations of collage and craft within the Pattern and Decoration movement. The exhibition showcases Schapiro’s pioneering work exploring early digital image production technologies, presaging contemporary artists’ practices today in the realm of feminist and digital art.

Miriam Schapiro's Fanfare (1958), Collection of the Jewish Museum, is on view in Masters of New York: The Generation of Rothko, Pollock, and Krasner.

The claim that painting is dead has been a common refrain among critics for decades. Nevertheless, artists have continuously pushed the medium forward. The Living End: Painting and Other Technologies, 1970–2020 surveys the arc of painting over the last 50 years, highlighting it as a mode of artistic expression in a constant state of renewal and rebirth.

Bringing together more than ninety works spanning six decades, Electric Op examines how artists have used abstraction to explore the relationship between perception and technology. While today considered an art historical “dead end” with few echoes in contemporary art, Op art in fact became the first artistic movement of the Information Age, paving the way for art to be abstracted into analog and digital circuits. Just as optical illusions help us “see” ourselves in the act of seeing, Op art can help us see how vision itself has been transformed by electronic media.

Radical Software: Women, Art & Computing 1960-1991 surveys the history of digital art from a feminist perspective, focusing on women who worked with computers as a tool or subject and artists who worked in an inherently computational way.

The exhibition features Miriam Schapiro's The Palace at 3:00 AM or Meander (1971).

Particles and Waves examines how concepts and technologies from the realms of advanced scientific research impacted the development of abstract (or non-figurative) styles of artwork in postwar Southern California.

The artists in Skilled, Subversive, Sublime: Fiber Art by Women mastered and subverted the everyday materials of cotton, felt, and wool to create deeply personal artworks. This exhibition presents an alternative history of twentieth-century American art by showcasing the work of artists who, stitch by stitch, utilized fiber materials to express their personal stories and create resonant and intricate artworks.

Non-Objectified presents a dynamic group of works by female artists operating under the umbrella of abstraction. The show’s title is a play on the term ‘non-objective’ painting, coined by by Alexander Rodchenko in 1918. This movement was centered in Europe and created in reaction to centuries of figurative representation, as practiced and espoused in the academies. Non-Objectified is a riff on Rodchenko’s term, a double entendre exploring female artists’ resistance to the objectification of bodies. The show takes the form of a dialogue between works by a cross-generational, international group of artists selected for their varying approaches to abstraction, each variation invoking or involving the body in subtle ways.

This exhibition is the first of two consecutive installations featuring the closely related techniques of collage, assemblage, photomontage, and found object sculpture. The diverse selection of artworks by leading national and international artists, drawn from Mia’s collection and local private collections, emphasizes the museum’s commitment to modern and contemporary art. The exhibition examines the resurgence of interest in these art forms during the postwar period and ensuing decades, highlights both formal and conceptual experimentation, and demonstrates how these interrelated techniques are particularly suited to exploring social, political, cultural themes and content.

At their core, creating and looking at works of art are acts of care, from the artist’s labor to the viewer’s contemplation and appreciation. Storage, conservation, and display are also ways of tending to art. This exhibition invites visitors to explore how contemporary artists trace and address concepts of care through their materials, subjects, ideas, and processes

There is no doubt Miriam Schapiro has received more attention and accolades in recent years than she had in the later period of her life. However, the urge to pigeonhole her into strictly feminist art movements, which many have, misses entire aspects of her creative output and her prescient and revolutionary approaches to new technology and art making.

At a panel discussion on April 26, conducted by Zoom from the Eric Firestone Gallery in downtown Manhattan, artists and art historians attempted to define her contributions in a more holistic sense and ask the important question of why she hasn't received her full due.

This exhibition—the first in the Museum’s history to have been fully developed and curated by an undergraduate student—features more than 50 contemporary artworks by women artists, with an emphasis on works created with unusual techniques or media.

Moderated by William J. Simmons | with Judith Brodsky, Carrie Moyer, Komal Shah, and Lisa Wainwright.

Held in conjunction with the exhibition Miriam Schapiro: The André Emmerich Years Paintings from 1957–76

Moderated by Elissa Auther | with Joyce Kozloff, Melissa Meyer, Beau R. Ott, and Mira Schor.

Held in conjunction with the exhibition Miriam Schapiro: The André Emmerich Years Paintings from 1957–76

"Too Much Is Just Right: The Legacy of Pattern and Decoration" features more than 70 artworks in an array of media from both the original time frame of the Pattern and Decoration movement, as well as contemporary artworks created between 1985 and the present.

With reproductive rights severely under attack in the U.S., and women’s bodies yet again a battleground, feminist artist Miriam Schapiro’s groundbreaking work becomes urgently relevant, again.

By the late 1960s, the women’s liberation movement was gaining traction throughout the United States, giving rise to the women’s health movement at the end of the decade. At the moment when activists urged women to take control of their reproductive health—often beginning with handheld mirrors, flashlights, and speculums—women’s art of the period similarly focused on the female reproductive system.

In the spring of 1963, the New York Art Committee for Tougaloo College established Mississippi’s first collection of modern art at Tougaloo, a historically Black college located north of Jackson. As civil rights protests swirled across the fiercely segregated state, the College became an unlikely hub of European and New York School modernism and a place that the collection’s founders envisioned as “an interracial oasis in which the fine arts are the focus and magnet.” Co-organized by the American Federation of Arts and Tougaloo College, Art and Activism traces the birth and development of this significant and distinctive collection. With approximately thirty-five artworks by artists such as Francis Picabia, Jacob Lawrence, and Alma Thomas, the exhibition brings renewed attention to a complex American collection established at the intersections of modern art and social justice.

Making Knowing: Craft in Art, 1950–2019 foregrounds how visual artists have explored the materials, methods, and strategies of craft over the past seven decades. Some expand techniques with long histories, such as weaving, sewing, or pottery, while others experiment with textiles, thread, clay, beads, and glass, among other mediums. The traces of the artists’ hands-on engagement with their materials invite viewers to imagine how it might feel to make each work.

This exhibition invites viewers to consider how size and repetition can be interpreted as political gestures in the practices of many women artists.

Taking Space: Contemporary Women Artists and the Politics of Scale examines the approaches of women artists for whom space is a critical feature of their work, whether they take the space on a wall, the real estate of a room through sculpture and installation, engage seriality as a spatial visual practice, cast a wide legacy in art history or claim the space of their body. This exhibition invites viewers to consider how size and repetition can be interpreted as political gestures in the practices of many women artists.

Featured artists include Mequitta Ahuja, Polly Apfelbaum, Jennifer Bartlett, Maria Berrío, Chakaia Booker, Emily Brown, Joan Brown, Tammy Rae Carland, Squeak Carnwath, Vija Celmins, Elizabeth Colomba, Njideka Akunyili Crosby, Eiko Fan, Louise Fishman, Audrey Flack, Mary Frank, Viola Frey, Hope Gangloff, Judy Gelles, Nancy Graves, Guerrilla Girls, Ellen Harvey, Clarity Haynes, Orit Hofshi, Barbara Kruger, Winifred Lutz, Vanessa Marsh, Ana Mendieta, Leah Modigliani, Elizabeth Murray, Wangechi Mutu, Alice Neel, Dona Nelson, Louise Nevelson, Ebony G. Patterson, Liliana Porter, Debra Priestly, Ana Vizcarra Rankin, Faith Ringgold, Mia Rosenthal, Brie Ruais, Betye Saar, Miriam Schapiro, Mira Schor, Alyson Shotz, Sylvia Sleigh, Becky Suss, Mickalene Thomas, Stacy Lynn Waddell, Marie Watt, Dyani White Hawk and Deborah Willis.

Featuring works from the permanent collection, including many recent acquisitions, Taking Space is one of three exhibitions at PAFA in 2020–2021 celebrating women artists in honor of the 100th anniversary of the passing of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which granted women the right to vote.

Where Art Might Happen: The Early Years of CalArts focuses on the legendary founding years (1970–1980) of the California Institute of the Arts, which has produced numerous well-known artists. This wide-ranging group exhibition presents a variety of perspectives on the school: parallel movements from the milieus of Conceptual Art, feminism, and Fluxus as well as the school’s radical pedagogical concepts will be brought together for the first time.

With Pleasure: Pattern and Decoration in American Art 1972–1985 is the first full-scale scholarly survey of this groundbreaking American art movement, encompassing works in painting, sculpture, collage, ceramics, installation art, and performance documentation. Covering the years 1972 to 1985 and featuring approximately fifty artists from across the United States, the exhibition examines the Pattern and Decoration movement’s defiant embrace of forms traditionally coded as feminine, domestic, ornamental, or craft-based and thought to be categorically inferior to fine art.

Ornament as Promise was the premise of the Pattern and Decoration movement in the United States (1975–1985). In this exhibition, mumok presents the rich collection of works from this movement of Peter and Irene Ludwig, in the largest presentation of Pattern and Decoration in German-speaking Europe since the 1980s.

Less Is a Bore: Maximalist Art & Design brings together works in painting, sculpture, ceramic, dance, furniture design, and more that privilege decoration, pattern, and maximalism.

Borrowing its attitude from architect Robert Venturi’s witty retort to Mies van der Rohe’s modernist edict “less is more,” Less Is a Bore shows how artists, including those affiliated with the Pattern & Decoration movement of the 1970s, have sought to rattle the dominance of modernism and minimalism. Encouraged by the pluralism permeating many cultural spheres at the time, these artists accommodated new ideas, modes, and materials, challenging entrenched categories that marginalized non-Western art, fashion, interior design, and applied art.

The medium of fiber is also weighted with gendered, socio-political signifiers that are imparted onto the final work of art. To put it plainly, fiber is feminine. Weaving, embroidery, knitting and sewing are thought to be the domain of women, whose productions in these areas have long been relegated to the status of “decoration.” Objects described in these terms traditionally do not fall into the rarefied, male-dominated Pantheon of “Fine Art,” which has long been the province of painting, drawing, sculpture and printmaking. But given the shift of values in contemporary culture, does this distinction hold true today?

In June of 2015, Miriam Schapiro, the pioneering feminist artist and founding member of the Pattern and Decoration movement, passed away at the age of ninety-one. Surprisingly, given her status as the elder stateswoman of the feminist art movement, the tremendous impact of her oeuvre on contemporary art has yet to be fully acknowledged or critically assessed. This exhibition seeks to redress this gap in the history of American art through an exploration of Schapiro’s signature femmages, the term she coined to describe her distinctive hybrid of painting and collage inspired by women’s domestic arts and crafts and the feminist critique of the hierarchy of art and craft.

MAMCO examined in this large group exhibition the “Pattern & Decoration” movement, formed in the 1970s and that enjoyed international success in the 1980s, before fading in the decades thereafter.

Patchworks and decorative patterns on the one hand and a political-emancipatory claim on the other – the Pattern and Decoration movement combines apparent contradictions. In the mid-1970s, the movement developed in the USA as one of the last art movements of the 20th century, brought forward by as many female artists as no other movement before. It was supported, among others, by feminist artists such as Joyce Kozloff, Valerie Jaudon, Robert Kushner and Miriam Schapiro.

For most of the last four decades, Pattern and Decoration art seemed wonderfully outré to many observers, an eccentric violation of the standards and norms of serious painting and sculpture that was itself not to be taken too seriously.

Nothing in art is more powerful than color. From Matisse to Mark Rothko and Frank Stella, and onward to the huge Color Field canvases and pulsing neon sculptures of today, color as a means of expression is the keynote for this wildly exuberant show.

Featuring work by thirty-six global artists, Women House challenges conventional ideas about gender and the domestic space. The exhibition is inspired by the landmark project Womanhouse, developed in 1972 by Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro. With works that disrupted traditional ideas about the home as a feminine realm, Womanhouse was the first female-centered art installation to appear in the Western world. In the new exhibition, Women House, women artists from the 1960s to today examine the persistence of stereotypes about the house as a feminine space.

In a 1989 interview, the artist Miriam Schapiro discussed her admiration for “heroines” like Virginia Woolf, Sylvia Plath, and Frida Kahlo. Noting their rather fraught lives, she said “that doesn’t stop you from expressing your point of view in whatever manner you choose to do it.” In the 1970s, Schapiro herself chose to make craft works that she termed “femmages” (a portmanteau of “feminine” and “collage”), which staked a claim for women, both in the art world and outside it, by centering the home as a site of resilience and subversion. And she certainly lived by these principles of resistance, deliberately situating her practice against artistic norms of her day.

Western art history is often viewed as a neat succession of individual artists and their singular masterpieces. This narrative runs parallel to the American story of westward expansion, propelled by the idea of individualism and independence. West by Midwest offers a messier alternative—one that illuminates the ways that contemporary art practices spread and develop by tracing the intersecting lives of artists who have migrated from the American Midwest to the West Coast since the mid-20th century. Lured by career opportunities, warmer weather, and the prospect of a better life promised by the postwar boom, artists in this exhibition attended art schools together, shared studios, exhibited work in the same galleries, collaborated on projects, engaged in activism, and dated. Following these crisscrossing lines of kinship, West by Midwest reveals social, political, artistic, and intellectual networks of artists and their shared experiences of making work and making a life.

Miriam Schapiro’s early collaborations are well-trod ground; her cofounding with Judy Chicago of one of the first feminist-art programs, at the California Institute of the Arts, in 1971 is legendary, and her part in coining the term femmage broke open linguistics for a burgeoning field of feminist art. But a particular association, with physicist David Nabilof, is understudied. Schapiro met Nabilof while both were teaching at the University of California, San Diego, in 1967, and together they explored the possibilities of then-nascent computer-aided design technologies. For a painter who was inculcated into the cult of Abstract Expressionist mark-making, this must have seemed a revelation—and the canvases on display in this eight-painting show are evidence of that fruitful dialogue.

Two exhibitions offer a broad overview of the 60-year career of influential first-generation feminist artist Miriam Schapiro, who died last summer at the age of 91. With Judy Chicago she established the CalArts Feminist Art Program in 1970 and organized the legendary CalArts “Womanhouse.”

“Miriam Schapiro, A Visionary,” at the National Academy is the artist’s first survey in New York and ranges from her de Kooning–esque fleshy Abstract Expressionist paintings of the ’50s to her gorgeous hard-edge acrylics of the ’60s to her subversive crazy-quilt florals, pinwheels, and fan collages of the Pattern and Decoration ’70s and beyond. Dollhouse (1972), which was included in “Womanhouse,” contains soft Oldenburgian kitchen appliances, a witty endless column of wine corks, and a tiny cloth doll—wearing Barbie’s plastic cowboy boots—that could almost have been by Louise Bourgeois.

There is a particular thrill in catching an artist in one of those rare moments when they are radically altering the premise of their own work and walking out on a limb, before the direction’s meanings and effects have become codiied within their own practice. The exhibition Miriam Schapiro, The California Years: 1967–1975 at Eric Firestone Loft offers a view into such a moment in the career of noted American artist Miriam Schapiro, in tandem with the concurrent survey, Miriam Schapiro, A Visionary, at the National Academy. These two exhibitions mark the first opportunity to consider Schapiro’s work since her death in June 2015, after a long illness. Each one examines Schapiro’s desire to develop a feminist aesthetic that would enact her politics in visual language.

“The California Years: 1967–1975” documents a momentous shift in Miriam Schapiro’s practice, from the wry, abstract feminist-futurism of her hard-edge paintings to the busy decadence of her mixed-media “femmages.” For her handsomely mod paintings in the former category, she used computer software to model and manipulate three-dimensional geometric structures. While the exhibition’s press release notes that these images are often “coded depictions of yonic forms,” we’re not talking about seashells and split melons here. In the pristinely painted Keyhole, 1971, a fiery red-orange and rose-colored mother ship approaches from a cloudless blue sky. The chic all-blue Horizontal Woman No. 2 from the same year slyly references a reclining nude with its blank virtual architecture. A kind of landscape, the painting depicts something resembling a compound of modernist bungalows built into a featureless hilltop.

Miriam Schapiro, a pioneering feminist artist who, with Judy Chicago, created the landmark installation “Womanhouse” in Los Angeles in the early 1970s and later in that decade helped found the Pattern and Decoration movement, died on Saturday in Hampton Bays, N.Y. She was 91.

Whitechapel Gallery presents a major exhibition of 150 paintings from an overlooked generation of 81 international women artists.