B. North Carolina, 1914

D. New York, NY, 2000

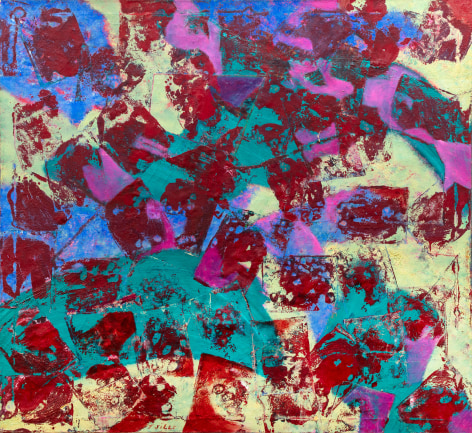

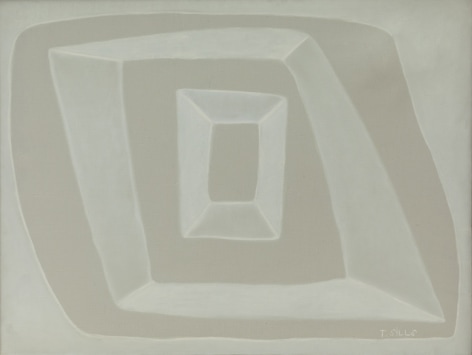

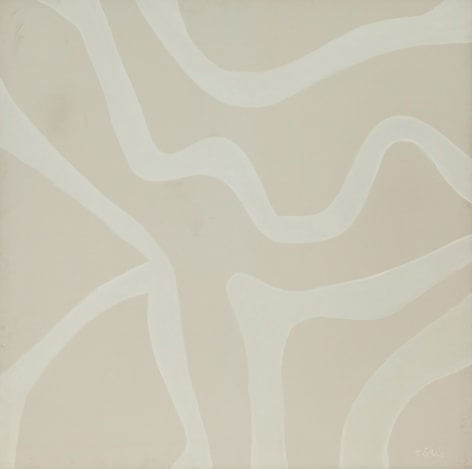

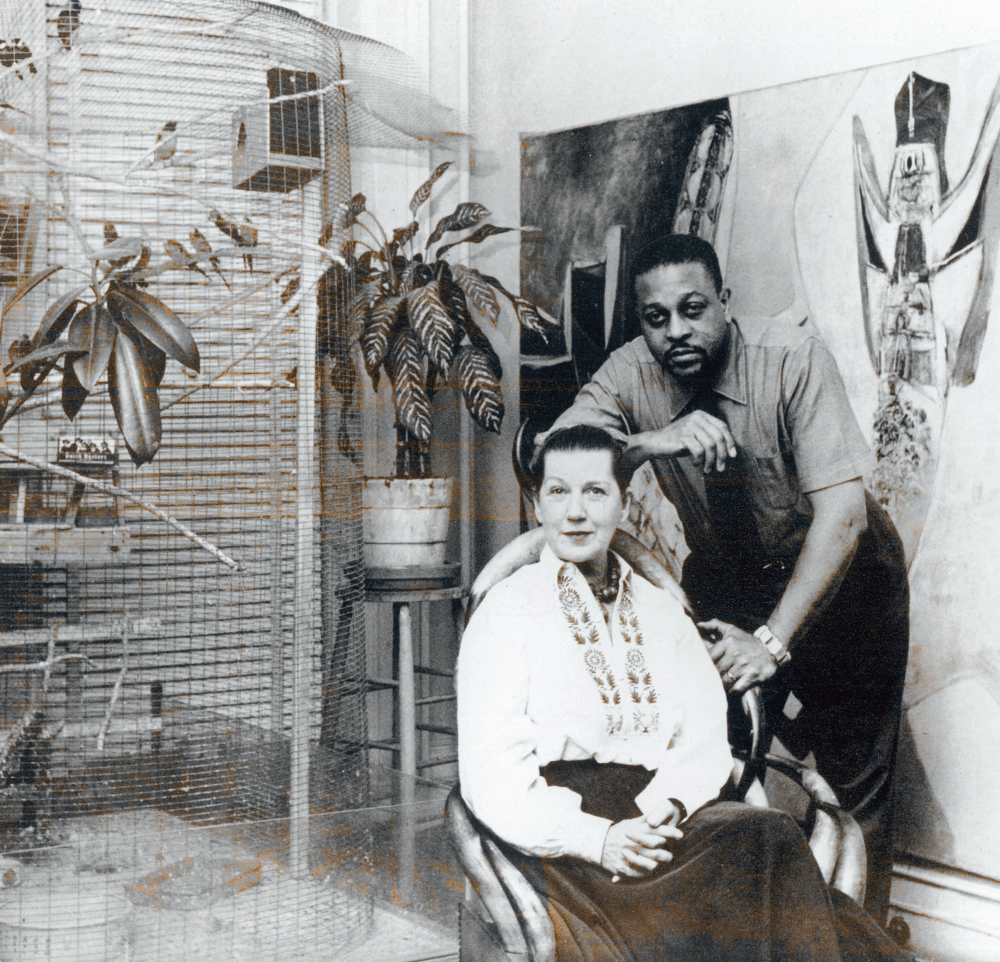

Thomas Sills began painting in 1952, inspired by his wife, Jeanne Reynal’s, work and collection of abstract art. He did not have formal training as an artist, but through Reynal he met a wide range of artists: from Marcel Duchamp and Max Ernst to Willem de Kooning, Barnett Newman, and Mark Rothko. Sills’s earliest paintings were experimental and employed an automatist approach; he used a variety of tools to apply paint and a diversity of materials on the surface of his paintings. By the late 1950s, he began working with an idea of equivalence between figure and ground, so that each form is both the positive and the negative of the form next to it. Often defined by a balance of just two colors, the compositions form radiating, optical sensations.

Thomas Sills

The Tree and the River, 1964

oil on canvas

68.0h x 69.0w in

172.72h x 175.26w cm

THSIL041

Speaking on his process, Sills remarked: "The main thing for me when I work is to say something worthwhile. My eyes must be open to see some of the good things. What I think about when I start painting is paint. A painter should paint only the way he wants to paint. There are no rules about it. I try not to destroy what comes out of my paintings. I don’t fight it but let whatever is there, come out."

Sills was the subject of four solo exhibitions at Betty Parsons Gallery in New York from 1955 to 1961. In 1962 he exhibited with Paul Kantor Gallery, Los Angeles; and had a two-person exhibition with Reynal at the New School for Social Research, New York. In the 1960s and early ‘70s, he showed with Bodley Gallery, New York. He was the subject of solo exhibitions at Creighton University, Omaha, NE; and the Art Association of Newport, RI. Sills was also included in several important historic exhibitions of African American artists in the 1960s and early 1970s.

His work can be found in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, all New York; along with the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, CA. Sills is represented by Eric Firestone Gallery where he was the subject of a major solo presentation, Thomas Sills: Variegations, Paintings from the 1950s–70s (2022); acclaimed by critic Martha Schwendener in the New York Times.

One of only a few African American participants in the abstract expressionist movement, Thomas Sills (1914–2000) has been largely overlooked until recently. Donated by John Pappajohn to the National Gallery of Art, the painting Flagship (1963) epitomizes the distinctive style and technique Sills developed to create elegant abstractions with a limited palette and disciplined forms.

In the spring of 1963, the New York Art Committee for Tougaloo College established Mississippi’s first collection of modern art at Tougaloo, a historically Black college located north of Jackson. As civil rights protests swirled across the fiercely segregated state, the College became an unlikely hub of European and New York School modernism and a place that the collection’s founders envisioned as “an interracial oasis in which the fine arts are the focus and magnet.” Co-organized by the American Federation of Arts and Tougaloo College, Art and Activism traces the birth and development of this significant and distinctive collection. With approximately thirty-five artworks by artists such as Francis Picabia, Jacob Lawrence, and Alma Thomas, the exhibition brings renewed attention to a complex American collection established at the intersections of modern art and social justice.

Thomas Sills (1914-2000) is, for many contemporary viewers, a discovery: Much of the work in “Variegations, Paintings From the 1950s-70s” at Eric Firestone was in storage before being mounted here. Sills was hardly unknown during his lifetime, though. He socialized with New York School painters like Willem de Kooning and Mark Rothko and had several solo exhibitions at the historically significant Betty Parsons Gallery before receding from the art world around 1980.

Sills’s paintings here include many of the traditional mid-20th-century New York School concerns. Abstract canvases with colored interlocking forms like “Travel” (1958) and “Son Bright” (1975) have a vibrant, dynamic tension similar to works by Lee Krasner and Piet Mondrian, who played with the painterly grid, and with the fleshy, promiscuous pink favored by de Kooning. Sills’s surfaces are also notable. He used rags instead of brushes to finish his paintings, and this gives the pigment a particularly even look, beautifully integrated into the canvas surface.

In February 1971, the newly formed Delaware organization, Aesthetic Dynamics, Inc., presented its first major undertaking: the exhibition of over 130 works of art—drawings, prints, photographs, paintings, and sculpture—by 66 African American artists. Numerous factors led to artist Percy Ricks’ founding of Aesthetic Dynamics and their ambitious inaugural exhibition, most notably the trauma suffered from the 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. and the subsequent nine-month National Guard occupation of Wilmington and Ricks’ desire to emphasize the influence of African American artists in Wilmington.

Now at its 50th anniversary, Aesthetic Dynamics, Inc. and the Delaware Art Museum are collaborating to revisit this momentous exhibition. Afro-American Images 1971: The Vision of Percy Ricks will include most of the artists who participated in the 1971 show, many known locally—Humbert Howard, Simmie Knox, Edward Loper, Sr., and Edward Loper, Jr.—as well as those recognized nationally including Romare Bearden, Sam Gilliam, Loïs Mailou Jones, Faith Ringgold, Alma Thomas, and Hale Woodruff. By rehanging the show as accurately as possible, the partnering organizations hope to examine the exhibition’s role in the Black Arts Movement as well as question why this seemingly successful event was largely neglected by historians in the decades that followed.